I've written elsewhere on the death of drawing; suffice it to say, over the course of my lifetime, I've watched hand drawing go from just about its midcentury peak in Western Civiliation to its virtual extinction in the twenty-first century. Hand drawing (and its offshoot, painting) once appeared in and on everything including newspapers, magazines, hardcover dustjackets, paperback, editorial illustration, advertising, album covers, billboards, signs on the sides buildings, and everywhere else. Except for a few specialty purposes like children's books, comics, and The New Yorker, imagery of the hand has almost completely disappeared as photography and digital technologies have conquered every realm.

Blurring the Boundaries between Text and Graphic, Word and Picture, Art and Culture

Showing posts with label illustration. Show all posts

Showing posts with label illustration. Show all posts

Sunday, August 8, 2021

Friday, October 3, 2014

Fun With Texture: Demo from a Cartooning Workshop

This sheet was drawn on Strathmore medium drawing 400 series 9" x 12" creme paper as a demonstration for a cartooning sketchbook workshop at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 2008. I enjoyed those workshops immensely. They were usually held in summer, although in recent years I became too busy with graduate school to be able to offer them. For years the museum refused to offer cartooning instruction, insisting by policy that educational offerings coincide with works on view in the museum galleries. Finally, in 2004, with the R. Crumb retrospective as part of the Carnegie International that year, I was invited to give instruction.

Since then the museum has canceled adult education workshops in drawing, painting, ceramics and other traditional media in favor of lectures relating to contemporary works of art. It is nothing short of tragic to see the museum art world forsake interactive drawing, the basis of all the visual arts (including architecture, cinematic storytelling/storyboarding, theatrical set and costume design, etc.) for passive dispensation of theory. The proper response to art is artmaking, not idle attendance at a lecture.

Two CMAs and the Second Commandment: A Digression

The current artworld, centered in public museums housed in large, monumental neoclassical buildings, have run the risk of succumbing to an ideology centered on their own self-importance as elite palaces of culture rather than democratic institutions of municipal and civic engagement. Cleveland's museum early in its history built a palace but emphasized education for all classes of Clevelanders, and despite the impulse to move to the right, has managed to successfully balance the two; but Pittsburgh, unfortunately, has not. Under its current leadership, Pittsburgh's CMA (as opposed to Cleveland's CMA) has embraced the ideology of contemporaneity in which various pseudo-Dada practices form the basis of high-flown intellectual discourse. But such mere pseudo-political conversations as can result from the contemplation of found objects, installations, performance and the like, while often interesting and verbally challenging, are rarely as rich as the contemplation of visual art that are works of the mind, as manually-generated images almost by the very means of their origins almost inherently are.

The mistake that over-educated, verbally-adept critics, curators, theorists, and art historians continually make is to disregard visual composition such as only the hand produces as thoughtless, or at least not as thinking on a level comparable with words. Old-fashioned craft, according to this ideology, is reserved only for the wordsmith and never the image maker, who is invariably regarded as a capitalist sell-out for rendering illusions corresponding to apparent reality, or at the very least mechanical and uncritical like a camera. Likewise, such honorifics as thinker and genius are reserved for the writer of texts, and even the title artist, when bestowed upon maker of conversation pieces, is not done without the most arch and patronizing irony. The bias for text over image runs very deep in our culture, going back at least to the Judao-Christian second commandment, which Max Horkheimer claimed as the basis and justification for contemporary critical theory.*

In any case, one hopes that the ascendance of logos and the iconoclastic impulse that has subtended much enthusiasm for modern and contemporary art over the past century or more will prove to be only a temporary aberration in our culture, and for a return of drawing to the educational environment of the city of Pittsburgh, and to the artworld nationally and internationally, in the very near future.

Since then the museum has canceled adult education workshops in drawing, painting, ceramics and other traditional media in favor of lectures relating to contemporary works of art. It is nothing short of tragic to see the museum art world forsake interactive drawing, the basis of all the visual arts (including architecture, cinematic storytelling/storyboarding, theatrical set and costume design, etc.) for passive dispensation of theory. The proper response to art is artmaking, not idle attendance at a lecture.

Two CMAs and the Second Commandment: A Digression

The current artworld, centered in public museums housed in large, monumental neoclassical buildings, have run the risk of succumbing to an ideology centered on their own self-importance as elite palaces of culture rather than democratic institutions of municipal and civic engagement. Cleveland's museum early in its history built a palace but emphasized education for all classes of Clevelanders, and despite the impulse to move to the right, has managed to successfully balance the two; but Pittsburgh, unfortunately, has not. Under its current leadership, Pittsburgh's CMA (as opposed to Cleveland's CMA) has embraced the ideology of contemporaneity in which various pseudo-Dada practices form the basis of high-flown intellectual discourse. But such mere pseudo-political conversations as can result from the contemplation of found objects, installations, performance and the like, while often interesting and verbally challenging, are rarely as rich as the contemplation of visual art that are works of the mind, as manually-generated images almost by the very means of their origins almost inherently are.

The mistake that over-educated, verbally-adept critics, curators, theorists, and art historians continually make is to disregard visual composition such as only the hand produces as thoughtless, or at least not as thinking on a level comparable with words. Old-fashioned craft, according to this ideology, is reserved only for the wordsmith and never the image maker, who is invariably regarded as a capitalist sell-out for rendering illusions corresponding to apparent reality, or at the very least mechanical and uncritical like a camera. Likewise, such honorifics as thinker and genius are reserved for the writer of texts, and even the title artist, when bestowed upon maker of conversation pieces, is not done without the most arch and patronizing irony. The bias for text over image runs very deep in our culture, going back at least to the Judao-Christian second commandment, which Max Horkheimer claimed as the basis and justification for contemporary critical theory.*

In any case, one hopes that the ascendance of logos and the iconoclastic impulse that has subtended much enthusiasm for modern and contemporary art over the past century or more will prove to be only a temporary aberration in our culture, and for a return of drawing to the educational environment of the city of Pittsburgh, and to the artworld nationally and internationally, in the very near future.

*See Max Horheimer, letter to Otto O. Herz, September 1, 1969, in Gesammelte Schriften, volume 18 Briefwechsel 1949-1973 (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 1996) p. 743; cited in Sven Lüttken, "Monotheism à la Mode," in Alexander Dumbadze and Suzanne Hudson, Contemporary Art: 1989 to the Present (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), pp. 304, 310, note 11. Lüttken attempts to make the rather unconvincing argument that a total ban on representative art is a valid form of criticism of the image and the proper role critical inquiry, suggesting the temperament of critical theorists.

For more on drawing, see The Withering Away of Drawing. For more on the Dumbadze anthology, see After Critical Thinking.

Sunday, August 10, 2014

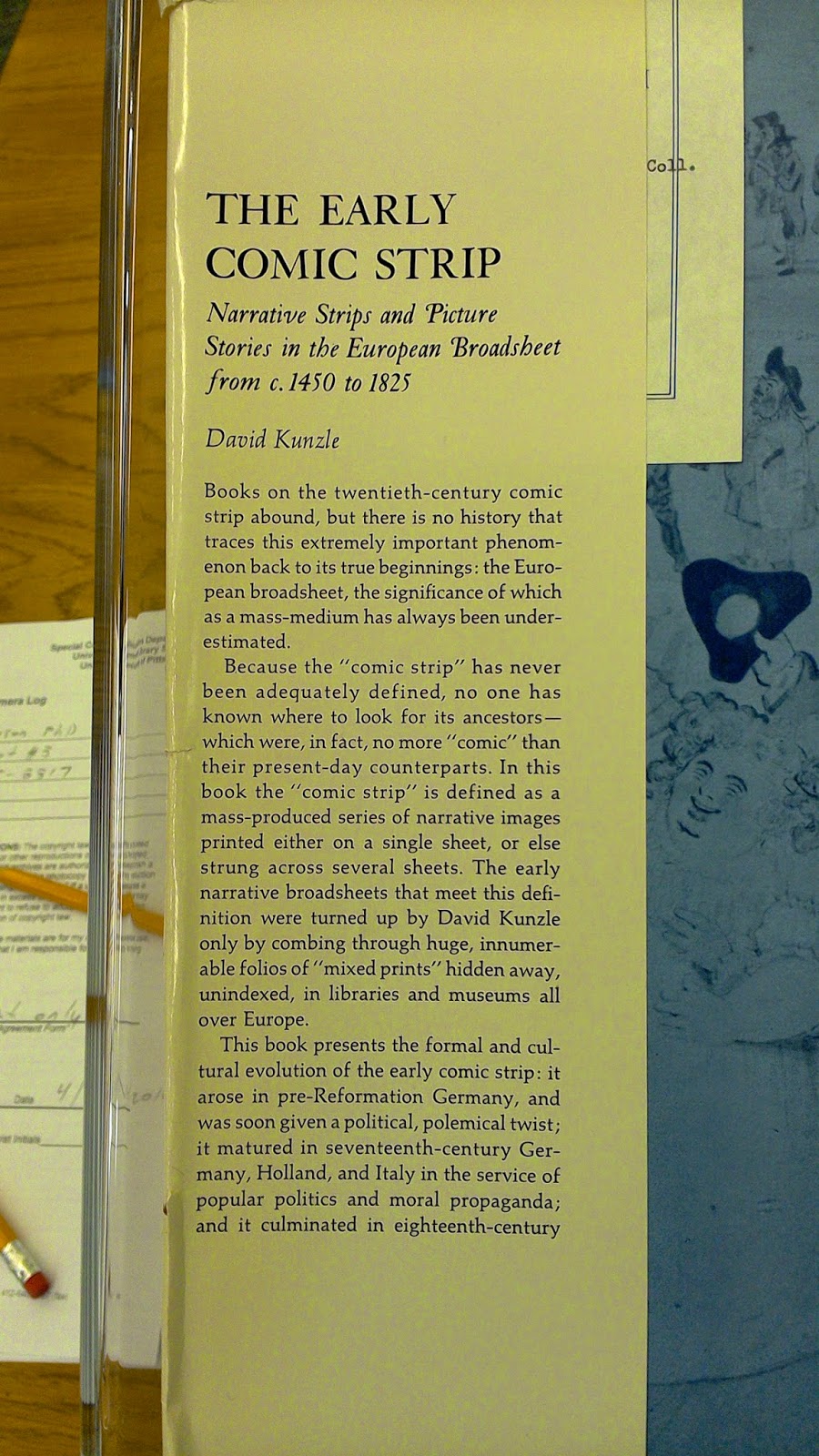

Kunzle’s Pre-History of Comics: But Is It Really?

The scholar David Kunzle declared in 1973 that he was

writing “a history or pre-history” of the modern newspaper comic strip. This

enterprise has come to encompass a significant portion of his professional scholarship,

including four major books with the term “comic strip” in the title: History of the Comic Strip, Volume I: The

Early Comic Strip—Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European

Broadsheet from c.1450 to 1825 (1973)[1]; The History of the Comic Strip, Volume II: The Nineteenth Century (1990)[2]; Rodolphe Töpffer: The Complete Comic Strips (2007)[3]; and

Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe

Töpffer (2007)[4].

These four volumes are preceded by one of Kunzle’s first published articles, a

translation of Francis Lacassin’s “The Comic Strip and the Film Language,”

which is augmented by almost 4 ½ pages of “supplementary notes” by Kunzle and

amounts to a prolegomena to Kunzle’s own scholarship on pre-twentieth-century

picture stories and their relationship with cinematic history.[5] Such

a sizeable corpus of research and writing,[6]

to say nothing of the publication of these sometimes cumbersome and profusely

illustrated works, would be a worthy if not magisterial achievement for any

scholar, particularly one working in such a pioneering area of graphic art as

pre-twentieth-century printed picture stories. However, the twentieth-century term

“comic strip” figures prominently in each of the titles mentioned, and Kunzle

in his own right has become considered a father of sorts to scholars of comics,

and has had a surprising and unexpectedly substantial impact on the way comics

are being perceived today.

So it may seem impertinent to ask: is Kunzle's undeniable

accomplishment really a history or pre-history of the comic strip? Does it do

justice to the pre-twentieth-century material Kunzle studies to be considered

primarily as comic strips or precursors to comic strips? What are Kunzle’s motivations

for claiming the term “comic strip” as his rubric, and would his material have been

better served by another term, such as “picture story”? What effect has

Kunzle’s work, and his assimilation of his material to the modern comic strip, had

on comics (both on its scholarship and the art form)? Would it be more productive,

in fact, for comics scholars and artists to think, not of earlier graphic

(printed) picture stories as latent comic strips (or comic books or graphic

novels), but of comics as a particular formulation or solution to the problems

presented by the graphic picture story? Would it be more productive for

twenty-first century creators to consider the creative potential of

combining words and pictures freely, with the entirety of the history of

culture offering suggestion, rather than reducing the history of all previous words-and-pictures

experiments down to a teleological, evolutionary drama narrowly concerned with

the perfection of a specific, marketable form of picture story?

|

| The reference room of the Frick Fine Arts Libary, University of Pittsburgh, which holds a copy of Kunzle’s History of Comics Volume I (not pictured). |

An informal search Google N-Gram search and search of databases at my disposal suggests that the term comic strip did not emerge as a term of description for the American newspaper feature we now know by that name until probably the mid-1910s. All the material Kunzle studies in his four major works dates from prior to the twentieth century. The few times that Kunzle mentions twentieth-century newspaper comic strips throughout this corpus, it is with at least mild disdain; he seems to regard the more popular successors to his material as an attenuated if not fallen and debased artform when compared to the earlier material he finds more richly varied as to subject matter and political and social viewpoint and consequently so much more engrossing. So why does he so emphatically embrace the term comic strip by placing it firmly in the titles of all his works, and why does he so earnestly want us to view the narrative strips, picture stories, broadsheets, and other material under scrutiny as comic strips?

Kunzle acknowledges more than once that his project was

inspired by the art historian Ernst Gombrich, who published his ground-breaking

Art and Illusion in 1960 (which is

still on some required reading lists).[7]

Gombrich is the first to make the connection between early print picture

stories (and specifically the work of Töpffe) to the modern newspaper comic

strip form. Gombrich asserts, “to Töpffer belongs the credit, if we want to

call it so, of having invented and propagated the picture story, the comic

strip.”[8]

Gombrich views Töpffer’s combination of words and pictures as especially prescient,

“In view of what has happened during the last decades,” presumably a reference

to the rising popularity of newspaper comic strips and children’s books

(Gombrich was writing in the 1960s).[9]

Gombrich, however, does not elaborate on the distinctions or definitions of the

terms “picture story” or “comic strip,” let alone recount the evolution from

one to the other.

Enter Kunzle, Gombrich’s student, who does explore this

terrain, and also assumes the elder scholar’s identification of Töpffer as a

key figure in the development of the form(s). Kunzle also, at least at the

outset, also assumes Gombrich’s terminological ambiguity (“the picture story,

the comic strip”). Kunzle himself claims to “use the terms picture story and

comic strip indifferently,” although he frequently refers to “the development

of the picture story and comic strip,”[10]

along with other terms, quite often, as if they were separate and distinct

forms demanding the covering of all bases.

Kunzle establishes his use of the term comic strip in the

Introduction to History of the Comic

Strip Volume I, although he never justifies or explains his choice, or

indeed, that he is making a choice. In the opening section, Kunzle considers a

range of terms used to describe the twentieth century newspaper feature,

particularly foreign variants such as Italian fumetti, the French bandes

désinées (drawn strip), and the German term Bilderstreifen and Bildergeschichte

(literally, picture strip and picture story, respectively), and the French term

bande dessinée. Kunzle blandly

asserts, “Of all these terms, ‘comic strip’ is the most commonly used for the

newspaper strip,” which he describes as “an artistic phenomenon.” He writes,

All over the Western world, the comic strip has become a major form of mass communication, a potent force in molding public opinion, an international language […] understood and enjoyed by the literate and semi-literate alike.

But Kunzle offers no rationale as to why the term “comic

strip” should be favored in describing this phenomenon, let alone why it should

be applied retroactively to graphic material prior to the advent of the

American daily newspaper.

The clear inference is that Kunzle is saddled with the term “comic

strip” whether he finds it appropriate or not for the pre-twentieth-century

material he is studying. And indeed, he finds in completely inappropriate,

arguing, “only the English language […] insists that ‘drawn strips’ are comic,”

while in fact

the truly comic strip [Kunzle’s emphasis] does not emerge until … late eighteenth-century England. At this stage of its development, however, I have preferred to use the phrase “caricatural strip” …. [Therefore] I never refer to the pre-caricatural (i.e. pre-1780) strip as the “comic strip,” even when it contains an element of humor. I generally use the terms “narrative strip” or “narrative sequence,” “picture story” or “pictorial sequence” (depending on the format involved) in order to stress the narrative role of the medium, which I consider primary.[11]

Kunzle finds formal similarities between the material of his

study and twentieth-century newspaper comic strips sufficient to justify the

connection previously made by Gombrich, and constructs a definition of the term

“comic strip” broad enough (most notably by not being dependent on the word

balloons) to justify its application to his material.[12]

However, Kunzle never again employs the term “comic strip” in History of the Comic Strip Volume I following

the Introduction.

Further, Kunzle’s anachronistic application of the term

“comic strip” to the material of his study is all the more puzzling, since he seems

to have little knowledge or interest in twentieth-century material, or in

discussing “comic strips” per se. Indeed, Kunzle rarely discusses twentieth

century newspaper strips throughout his oeuvre, and then only generally and

vaguely, usually only with broad reference to their popularity, and often with

a good deal of disdain for what he sees as an artistic devolution from the rich

social commentary and propaganda of his favored era into banal soap opera and

gags of the time of his writing. Kunzle is also dismissive of the historically uninformed

“Compilers of books on the twentieth-century comic strip” and their “potted”

histories.[13]

For example, Kunzle blasts a biography, “that modern stalwart, Milton Caniff,” for

the name-dropping pretentions of its subtitle (“Rembrandt of the Comic Strip”),

and the author’s ignorance in conflating Renaissance cartoons (preparatory

drawings for paintings or tapestries) with the modern graphic form.[14]

Kunzle expresses no interest in extending his own research into twentieth

century material, to write a corrective history of twentieth century comic

strips, or even to compare examples of the pre-1896 material of his study with

more recent examples.

In fact, Kunzle seems to have regretted his choice of

placing the term “comic strip” in the title of his history of broadsheets and

picture stories. In the Preface to History

of the Comic Strip Volume II (1996), Kunzle goes on an extended,

unscholarly rant about the problems the term “comic strip” has created for the

reception of his scholarship in the intervening two decades.

As a respectable academic I have, I suppose, sought to give the comic strip academic respectability. I doubt that I have succeeded yet. The “scientific literature” of my discipline (art history) has tended to pass by Volume 1, The Early Comic Strip, no doubt because of its frivolous title, which has not convinced even the (nonacademic) celebrants of the genre in the 20th century that there is indeed a comic strip worthy of the name before the Americans “invented” it in 1896 or so. I was recently sent a script for an ambitious television series on the (20th century) comic strip, for which funding was being sought and to which I was nominated a “scholarly advisor.” The script started with the assertion that the first comic strips appeared in American newspapers at the end of the 19th century. Of course. By now I should have learned that to deny in the face of the U.S. media that the United States invented the comic strip is about as pointless as denying that the United States invented freedom and democracy. So I look once more to academe, which should understand that the real title of the present volume is “The acquisition and Manipulation of New Sites of Comoedic [sic] Narrative Discourses and Significations by Volatility-prone Social Sectors.” A big book should have a big title anyway.[15]

Kunzle further laments that his two-volume prehistory of the

comic strip “has been a lonely endeavor in many ways, just how lonely I can now

measure, in retrospect, as I enter the well-established field of 17th century

Dutch art.”[16]

More well established, and presumably more academically respectable.

|

Fischer von Erlach’s Entwürf einer Historischen Arkitektur (inventive history), 1721, showing the Halikarnassus plate.

|

Nonetheless, Kunzle retains the term “comic strip” for the title of his second mammoth volume, and more freely and boldly uses the term in discussing nineteenth-century material, even while acknowledging its anachronism. He muses,

The comic strip in the 19th century, for all its popularity, is without a recognized name. Töpffer called his comic albums either “picture novels” or, deprecatingly, “little follies.” In the trade they were called “caricatural albums,” or the “série Jabot,” after the initiating title. Töpffer himself pretended anonymity, which the pirates all too scrupulously observed. It is as if Jabot, the social upstart, having forced himself and his upstart graphic genre upon the public, was forever to be denied the dignity of a distinct literary or artistic category.[17]

Kunzle, to his credit, would stick with his guns, and even

more boldly assert the term “comic strip” in the titles of his two subsequent

publications on Töpffer.

But why did Kunzle initially adopt the term “comic strip” in

the early 1970s? Kunzle seems to have made the pragmatic calculation that

labeling his research on broadsheets and picture stories a “history or

pre-history of the comic strip” would be of benefit to his scholarship both

academically and in terms of landing a publisher for what was no doubt a

prohibitively expensive undertaking. In the post-war era, after cinema and

jazz, the comics strip seemed next in line as the American art destined for

academic validation and publishing success. Several decades had elapsed since

Coulton Waugh’s The Comics (1947),

but in the first half of the 1970s, the first of a new wave of comic-strip

histories were beginning to appear, or were being readied for publication.

These included Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson’s anecdotal anthology All in Color for a Dime (1970)[18];

Les Daniels’ Comix: A History of Comic

Books in America (1971)[19];

Marvel artist Jim Steranko’s two-volume The

Steranko History of Comics (1970, 1972)[20];

Arthur Asa Berger’s sociological study The

Comic-Stripped American: What Dick Tracy, Blondie, Daddy Warbucks and Charlie

Brown Tell Us About Ourselves (1973)[21];

and Jerry Robinson’s The Comics: An

Illustrated History of Comic Strip Art (1974)[22].

Kunzle may even had been aware of Maurice Horn’s The World Encyclopedia of Comics (1976), then in preparation.[23]

An important hint may lie in the fact that the Preface to History of the Comic Strip Volume I, dated 1968, contains no reference to or use of the term “comic strip” all, only “picture story” (twice).[24] But the volume was not published by the University of California Press until 1973, a five-year interval encompassing not only the publication of most of the comic strip histories listed above, but also Kunzle’s translation of the Lacassin article for Film Quarterly, also a UC publication (1972). The titling of the History of the Comic Strip Volume I and the writing of its Introduction, which uses the term “comic strip” more than 30 times (nowhere else in the volume does the term appear) may have taken place only after the Preface and body of the volume had been complete in 1968. The foregrounding of the term “comic strip,” for which Gombrich had already paved the way, may have belatedly occurred to Kunzle or been suggested by his publisher in recognition of a “comic strip” trend in publishing that had emerged since 1968. Such a move would not have been merely a cynical ploy to make the publication of the mammoth volume more feasible, but could have also been a sincere effort to connect Kunzle’s rather obscure study of broadsheets and picture stories to more current (and more sexy) scholarly discourses, particularly cinema.

This is most emphatically suggested by Kunzle’s 1972 translation of Lacassin for Film Quarterly. The introduction to the article, set in large bold italic that upstages the body text, presents the article not only as a precursor but also an unprecedented plug for Kunzle’s forthcoming History, and explicitly ties Kunzle’s work to the “intellectual respectab[ility]” belatedly emerging for comics that had been established for film “three or four decades ago.” The notes added by Kunzle, “which qualify some of Lacassin’s findings,” are half as long as Lacassin’s text.[25] Kunzle begins,

This is not the place to quarrel with Lacassin’s

assumption, which is so widely shared, that the comic strip and cinema were

born at the same period. Since the material has simply not been available

hitherto, critics cannot know that, in fact, the narrative picture strip

reached a certain maturity in German, Dutch, and English broadsheets in the

seventeenth century. In my book, which the University of California Press will

shortly publish, I reproduce an extensive corpus of these remarkable early

picture stories, which will thus become available for analysis and discussion.

Nor need we at this point question by what feat of logic Lacassin makes the

“birth” of the comic strip postdate by two generations one of the recognized

“fathers” of the art (for Gombrich, the

father), Rodolphe Töpffer.[26]

Whatever his reasoning or motivation for declaring his work “a

history or pre-history” of the comic strip, Kunzle stuck to his guns, using the

term “comic strip” in the title of two more scholarly publications on Töpffer.

It is now common, in fact, to see references in academic art historical

publications and museum exhibition catalogs to Töpffer as father or inventor of the comic strip.[27]

But as Geoffrey Batchen reminds us in the case of the history of photography,

such determinations are suspect. He remarks that historians

continue to squabble over which of them was the first to discover the one, true inventor of photography. […] [T]his is invariably an argument as much about virility and paternity as about history, as much about the legitimacy of both photographer and historian as historic primogenitors as about the timing of the birth itself.[28]

To the extent that Kunzle’s work is seen as foundational to

comic strip and comic book scholarship, his legacy is a mixed bag. The

unfortunate example of Kunzle’s snarky Preface to Volume II, mentioned above, as well as its Introduction which dwells at length on the status of nineteenth

century picture stories as a “childish genre,”[29]

suggests that a cloying desire for “academic respectability” has been passed

down to more recent scholars who continue to openly bitch, “Why Are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization?”[30]

On the positive side, as David Carrier attests, “I admire Kunzle, a bold and

original scholar, for gathering these materials, without which my own

philosophical study [on comics] could not have been conceived,” but departs

from Kunzle on the issue of word balloons.[31]

The more substantial implication being that Kunzle’s scholarship is not about

comics at all, but something that predates comics historically, and if anything

chronicles part of a pictorial and textual tradition that is larger than

comics.

To the extent that Kunzle’s scholarship is a rebuke of

twentieth and twenty-first century comic strips, comic books, and graphic

novels (and there is plenty of ammunition for such an argument throughout Kunzle’s four major works on pre-twentieth-century picture stories),[32]

and a prompt to live up to the larger pictorial and textual tradition that is Kunzle’s concern, this

admonition might be stated in a more effective way. Instead of saying comics

should be better than they are, one could simply say, stories told in words and pictures don’t have to be comics. Perhaps

that is the far greater lesson to be derived from Kunzle’s work.

[1] David Kunzle, History of the Comic Strip,

Volume I: The Early Comic Strip—Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the

European Broadsheet from c.1450 to 1825 (Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1973).

[2] David Kunzle, History of the Comic Strip,

Volume II: The Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1990).

[3] David Kunzle, ed., trans., Rodolphe Töpffer: The Complete Comic Strips

(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

[4] David Kunzle, Father of the Comic Strip:

Rodolphe Töpffer (Jackson

: University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

[5] Francis

Lacassin, “The Comic Strip and the Film Language,” trans. with additional notes

by David Kunzle, Film Quarterly, vol.

26, no. 1, (Autumn 1972), pp. 11-23. Kunzle’s footnote on p. 11 reads as

follows: “Translated from Lacassin’s Pour

un neuvième art: la bande dessinée (Paris: Union Generale, 1971) and his

preceding article “Bande dessinée et langage cinematographique,” Cinema ‘71, (September1971), by

permission of the publishers. The material has been slightly abridged from its

longer version in the book, but incorporates the refinements Lacassin made in

the book.” Kunzle’s additional notes occupy the final 4 ½ pages of the article,

set at the same type size as translated text, pp. 19-23.

[6] For brevity, these works will be referred to hereafter as History I and II, Complete, Father, and “Lacassin.”

[7] See Kunzle, History vol. 1, preface,

and Father, p. ix.

[8] Ernst Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study

in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, 3rd ed. (Princeton:

Bollingen, 2000 [1960]) p. 336.

[9] Gombrich, p. 337.

[10] Father, quotes from pp. xi and 53

respectively.

[11] History I, p. 1.

[12] History I, p. 2-3. David Carrier, among

others, takes issue with Kunzle, claiming “The speech balloon is a defining

element of the comic [strip].” See David Carrier, The Aesthetics of Comics, (University Park: The Pennsylvania State

University Press, 2000), pp. 3-4; quote p. 4.

[13] History I, p. 1.

[14] History I, p. 2.

[15] History II, p. xix.

[16] History II, p. xx.

[17] History II, p. 6.

[18] Dick

Lupoff and Don Thompson, eds., All in

Color for a Dime (New Rochelle NY: Arlington House, 1970).

[19] Les

Daniels, Comix: A History of Comic Books

in America (New York: Bonanza Books, 1971).

[20] Jim

Steranko, The Steranko History of Comics,

vols I and II (Reading PA: Supergraphics1970, 1972).

[21] Arthur

Asa Berger, The Comic-Stripped American:

What Dick Tracy, Blondie, Daddy Warbucks and Charlie Brown Tell Us About

Ourselves (New York: Walker, 1973).

[22] Jerry

Robinson, The Comics: An Illustrated

History of Comic Strip Art (New York: Putnam, 1974).

[23] Maurice

Horn, The World Encyclopedia of Comics

(New York: Chelsea House, 1976).

[24] History I, Preface [n.p.].

[25] The introduction or abstract of the article reads, in bolder and larger type than

the article, “The comic strip is now becoming intellectually respectable in

somewhat the same way that film did, three or four decades ago. Studies of

contemporary strips abound; serious artists are using the form for their own

purposes-often, of course, satirical purposes. As the French historian Francis

Lacassin argues in the pioneering article below, the “language” or syntax of

the comic strip shows many similarities to (and certain historical priorities

over) the language of film. The article has been translated by David Kunzle,

author of the forthcoming The Early Comic

Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet, c.

1450-1826—a sociocultural history of the first mass medium’s origins—and he

adds notes of his own which qualify some of Lacassin’s findings and extend them

even further back in time.” See Lacassin, p. 11.

[26] Lacassin, p. 19. The Lacassin article and its influence on comics

scholarships merits a discussion of its own, which in fact I first essayed on

an earlier incarnation of this blog around 2005. I plan to revisit that article

and repost soon.

[27] See for example Laura Hoptman, Drawing Now: Eight Propositions (New York:

Museum of Modern Art, 2002), p. 129.

[28] Geoffrey

Batchen, Burning with Desire: The

Conception of Photography (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1997), p. 35.

[29] History II, pp. 2-4.

[30] Thierry Groensteen, “Why Are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization?”

in Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester, eds., A

Comics Studies Reader (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi Press,

2009), pp. 3-11. [I discuss this article in a previous post on this blog.]

[31] Carrier, pp. 3-4; quote p. 3.

[32] Not

to mention Kunzle’s translation of Dorfman and Armand Mattelart’s 1973 Para leer al pato Donald into English as

How to Read Donald Duck in 1975,

suggesting that if Kunzle were to regard modern comics at all, their status as

capitalist commodities would be foremost in his critique.

|

| Back dustjacket flap of Kunzle's History of the Comic Strip Volume II: The Nineteenth Century, at the Special Collections room, Hillman Library, University of Pittsburgh. |

Saturday, July 12, 2014

Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Afterlife (and Somewhat Problematic Comic Book)

This continuous traveling through a Savage land enabled me to see what I might otherwise have missed. The Savage supersagas are apocalyptic.

Philip José Farmer, Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life

I have already commented on the first two issues of Dynamite’s

Doc Savage adaptation by Chris

Roberson and Bilquis Evely, in which I questioned whether the property could be adapted to any other medium; now I have seven of the eight issues in hand, and I will comment on this particular effort as constructively as I can. I

will start with the covers by Alex Ross, which emulate those of James Bama, one

of the great paperback illustrators of all time, whose covers graced most of

the Doc Savage covers through the late 70s, as well as countless westerns, and

at least the first memorable James Blish Star

Trek adaptation. I will then proceed to the story and interior art.

For the most part, Ross’s Bamaesque painted covers hew to

the James Bama formula for the Bantam paperbacks of the 60s and 70s. Stylistically,

they are all recognizably rendered in Ross’s Ross’s trademark watercolor

technique, which comes as close as humanly possible to mimicking Bama’s oils (perhaps

a 9 out of 10); had they been reduced to paperback size the effect might have

been greater still. As it is, however, at comic book size there is a certain roughness

and sharpness to the technique that cannot be overcome (watercolor demands a

certain spontaneity that cannot be overworked), and so they look like

watercolors trying to be oil paintings. Compositionally, the better covers

(that is to say, those that most effectively emulate Bama) show the single

figure of Doc facing some seemingly insurmountable menace.

Among the weaker covers, from the standpoint of evoking

Bama, are covers #1 and #8, which compress time in a mosaic of images, or depart

from the Bama formula in some other way. The second cover, one of the stronger

ones, completely fetishizes Doc’s trademark torn shirt, transforming it into a

swirling, flame-like maelstrom. Here Ross is at his most insightful, as he makes

explicit in almost parodically the underlying metaphorical function it served

in so many Bama covers, not as a literal shredded garment, utterly superfluous in

its failure to protect or to conceal, but as a motif of lightning-like energy

clinging to a superbly well-developed physique. The third cover shows a nuclear

explosion, an apocalyptic situation about which Doc can do little, and

therefore a bit more fatalistic than the Bama formula would ever allow. The

fourth shows Doc carrying a young Brit punk to safety from a burning field of

oil wells while splashing through puddles of spilt crude, the generational juxtaposition

presumably providing the interest, but coming off more like a typical Don

Pendleton Executioner cover. The

fifth cover features Doc in a Sterankoesque pose as a Skylab-like orbiting

satellite destroys the earth as if it were Krypton (again, like the nuke cover,

a theme that would have been a little too fatalistic for a Bama cover). The

seventh cover successfully evokes the cool color schemes often done to such

success by Bama, but features a rather a weak crowd composition that is

reminiscent of some of the weaker covers that graced the Bantam paperbacks by

either Bama or other artists.

The sixth cover, however, is clearly the most iconic of the

Dynamite series, and perhaps one of the most arresting Doc Savage images ever

created by any artist. It certainly ranks as the most memorable of any outside

the Bama canon, and outdoes a number of Bama Savage covers as well. It is a metaphoric contemplation of Doc

Savage facing a situation clearly distilled from 9/11, showing one horrific

aspect of that event as nine airliners nosedive out of the skies at once, Doc

powerless to save them. Fatalistic, yes, but not completely apocalyptic, and

perhaps summing up the theme of the entire series.

|

| Alex Ross, cover to Doc Savage #6, perhaps the most iconic image of the adventurer ever created. |

[The alternate covers, most of which presumably are intended

to evoke the various comic book iterations of the property, are not as successful, in my humble estimation. I haven’t purchased any of them and I won’t

comment on them any further. Sorry to be so dismissive, but them’s the breaks.]

As for the story itself, in contradistinction to the covers,

ironically Doc is almost never alone to face or solve a problem by himself.

From the beginning, the emphasis is on the team. Just as The West Wing served as a narrative antidote to all those

presidential histories in which one lone figure is the main protagonist, this Doc Savage seems bent on showing how

reliant Clark Savage, Jr. is on his teams of experts, from the original

Fabulous Five to the progressively younger and more racially, ethnically,

culturally, and genderally diverse and numerous aides that replace them as they

age, wear out, and (off stage, as it were) quietly pass away. As things

progress, even these nominally-individualized characters (each is given a

suitably corny nickname in the tradition of Monk, Ham, Long Tom, et al, but only

perhaps the young Brit punk is more that one-dimensional) give way to impersonal

cubicled call centers with 1-800 numbers and armies of anonymous analysts and coders,

and finally to an automated smart-phone network susceptible to meddling. In

fact, the general theme of the story would seem to be little more than a

demonstration of how the world has become a more complicated place since the

Street and Smith pulps came to an end, and more explicitly about how the scientific

and technological systems put in place by Doc, as well as his moral philosophy,

can by hi-jacked when put on auto-pilot.

This conception seems to owe something to Alan Moore’s Watchmen, which featured a Doc-like

Ozymandias depicted as a bureaucratic capitalist presiding over an

international corporation, who loses his moral perspective as the business

structures he has built ostensibly to solve the world’s problems become more

complex and unmanageable. In fact, Chris Roberson’s Doc only seems to appear in

scenes in which he can moralize and defend his questionable practices, such as

the secret Crime College, where criminals are medically “cured” of criminality

through a deft brain incision, and Doc’s general practice of working on his

scientific breakthroughs in secret and keeping them to himself. In other words,

even as Doc’s security network becomes more corporate and bureaucratic, his

intellectual property becomes increasingly proprietary, with disastrous

results. A major plot element concerns the secret serum that Doc perfects that

essentially makes him immortal, but is lost before it can benefit the world.

It is worth pointing out that both the immortality serum and

the moral implications of the Crime College are ideas borrowed from Philip José

Farmer, who suggests them in his pseudo-biography of Doc, Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life. Thus Roberson to a great extent is elaborating on a universe

outlined by Farmer as much or more than Kenneth Robeson, the original architect

of Doc’s adventures.

It is perhaps less useful to point out that such ambitious

themes as Roberson seems to have in mind might have been better explored in prose

than in comic book form, and perhaps more freely in a satire such as Farmer did

on several occasions with his more obsessively sexualized Doc Caliban (particularly

in A Feast Unknown), or as Moore does

rather succinctly with Ozymandias. In fact, given the “quick-read” mode of the

day compared to more densely-packed comics of past eras, the entire series so

far reads rather like a series of truncated scenes from one of the supersagas

(Farmer’s term) than one of the supersagas themselves, and not even

particularly pulse-pounding highlights from an average one. The pulp form,

after all, is nothing if not one break-neck cliff-hangar after another that in

retrospect bears little logical scrutiny, while the informational and action through-put of comics these days is little more than a smoke signal. While the series maintains readerly interest,

little of the visceral, no-holds-barred pulp spirit of the original stories is

in evidence. If one can imagine Doc’s hypothetical career since 1949 as being even

half as rich as his monthly exploits of the 30s and 40s, one could certainly

imagine distilling a richer and more exciting comic book therefrom. Instead, the Dynamite Doc Savage is a rather plodding, often slowly-paced, and above all

a hyper-conscious cerebral exercise that reads more like a rather dry storyboard

for what could be a more interesting feature film, than a comic book. One might

wish at least for a text page per issue musing at length on some of these

themes, and at least some historical background on the property to serve as

introduction for new readers and reminder to some of us old-timers who may

not have read an actual Savage in

quite awhile.

What Roberson seems to have in mind instead is a

meta-narrative of sorts that not so much adds onto or adapts the Doc Savage supersagas as takes a step

back from it to contemplate the more philosophical aspects of the superman-in-the-modern-metropolis theme, whose own hallowed belief in inexorable progress becomes

the ultimate evil and whose adversaries are less and less freelance madmen bent

on taking over the world and increasingly former aides who lose faith in Doc and his principles and

turn traitor. Doc’s righteous crusade instead of bringing the world to

salvation instead promulgates a self-fulfilling prophecy and induces a self-inflicted

apocalypse (although we’ll have to wait for the final issue for the outcome). Again,

these are great themes that could be better explored in prose, but given the problematics

of licensing the Doc Savage property and

the marketing prospects of publishing further text novels in that series, it is

likely that such a philosophically-tinged prose project would be unfeasible,

and a comic book adaptation that wants to suggest a movie treatment is the best

we can hope for.

Finally, the art of Bilquis Evely, which I commented on

previously and which seems more progressively likeable. I have sympathy for the

task she faces, evoking several periods of style and architecture, from 1933 to

the present. Her Doc paradoxically never rips his shirt, although he looks as

though he’s about to burst out of his suit on several occasions, particularly

when he addresses JFK’s cabinet. One gets the impression that she would rather

draw strapping, mostly-naked superheroes (as would we all) rather than

pedestrian fashions, quotidian props, and faithful portraits of famous

buildings. Many of her panel and page compositions seem static, owing to the

eye-level camera angles and vertical postures of most of her figures, and she

would do well to revisit John Buscema’s How

to Draw Comics the Marvel Way (the visual codification of the break-neck

pulp prose style). Her Doc is hardly dynamic let alone apocalyptic, but as a

first professional effort as this reportedly is, the Dynamite Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze is a

respectable accomplishment.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)