The biggest problem with the Fantastic Beasts film franchise, and it has been the biggest problem from the start, is that the films lack big, fat J.K. Rowling books to precede each film.* This was the winning formula for the Harry Potter films, and it was no secret—J.K. Rowling is an author, and Harry Potter was, first and foremost, a literary experience. Readers immersed themselves, wallowed, in books that progressively got longer; filmmakers boiled those books down, with more or less success, into crowd-pleasing feature films.

The Harry Potter series of films, one of the most successful franchises in film history, also came 100% pre-spoiled, as it were: Everyone had already read the books, digested the stories, and knew exactly what to expect going into the movie theater. The only drama and suspense, in some sense, was whether the filmmakers and performers could live up to the overwhelmingly high expectations of a massive, pre-sold audience—could compete, in other words, with reader’s imaginations. That the films met and in some regard exceeded such expectations—due in part to the serendipitous arrival of advanced digital special effects technology, without which the Harry Potter films would have looked like cheap, B-movie creepshows of an earlier generation—is what won over fans of the books, in turn spreading the Harry Potter phenomenon to new readers.

After completing her million-word opus, the author made it clear she had written enough prose on the subject, and except for a slender fundraiser and the occasional retcon pronouncement on social media, was done using her valuable brainspace on the world of Harry Potter. New dramatic productions would have to suffice essentially on gas fumes—a few backstory allusions and inferences derived from the Harry Potter book series.

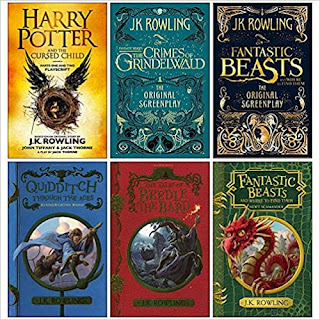

By going straight to threadbare screenplays, the author has been taking a big, fat shortcut in her own proven, world-beating strategy. Despite the publications of those inflated screenplays as bloated pseudo-books, readers were not fooled; their author had abandoned them. That was the main problem, from a reader’s perspective, with The Cursed Child, despite however much it might have entertained on the stage—as a book it read like bad fanfic and as a publishing event it amounted to a colossal artistic rip-off.

It is perfectly understandable, given the author’s purported burnout after The Deathly Hallows, that another big, fat book about her retroactively-branded “Wizarding World” was just too much. But the big, fat shortcut she continues to take, not only with The Cursed Child stage play but with the pseudo-epic Fantastic Beast films, rings hollow to her readers; it’s like a parent telling the children she’s temporarily separated from Daddy while flagrantly conducting an affair with another partner.

Why on Earth the author of Harry Potter would rather write big, fat potboilers about a BBC TV detective (under another male pen name, Robert Galbraith—the gender-obscuring initials “J.K.” not being pseudonym enough), rather than write the intricate backstory of Albus Dumbledore is simply inexplicable to most fans. What could lend itself more to a novelistic, big-fat book treatment than the grown-up, psychologically and historically nuanced world she is apparently attempting to convey in Fantastic Beasts? And what would lend itself least to cursory screenplays-direct-to-special-effects-movies?

|

| Along with her muddled and unhelpful views on gender issues, these are some of the big, fat books the author hasn’t had the time to give her full attention (one feels). |

Which leads to the other problem with Fantastic Beasts: a complete lack of children and young adult characters. The key to success of Harry Potter was its child-based fantasy and coming-of-age story that all ages of reader could enjoy. The Fantastic Beasts films not only deprive millions of readers of the big, fat books only the author could provide; it also replaces adorable children with various morose, fucked-up adult characters—characters for whom, one feels, it is too late— whose issues desperately needed to have been untangled in big, fat YA books that were never written.

Additionally, the few surprises, twists, and turns the post-Harry Potter films provide all seem ad hoc, superficial, improvised, thrown in—of questionable merit as artistic choices and of dubious authenticity in terms of the author’s world-building simply because they didn’t first make their appearance in a big, fat book. Most notable is Dumbledore’s sexuality—an aspect of the character fans regard almost as non-canonical, not because of any verdict on that sexuality but simply because the author never felt it worthy of in-depth, psychological exploration in prose.

Whatever conceptual material the new films have introduced seems slight and trivial compared to how each book and film in the Harry Potter series advanced an understanding of an elaborate, complex, growing fictional world. Each installment of the original was groundbreaking and mind-expanding, whereas the new films feel like filler material left on the cutting room floor—and with good reason. Epic books were the fundamental pillar of the epic film series; without that foundation, the pseudo-epic films feel hollow.

The dilemma can be reduced to a very simple question: If the Fantastic Beasts stories are not worth eighteen months of the author’s time to contemplate, draft, and rigorously revise into big, fat (and presumably bestselling) books, are they really worth $200 million each—not counting ad budget—to produce as movies?

The parallel issue, of course, is that with all this extra time on her hands, the author has also indulged her half-baked sociological tendencies by making pronouncements on gender issues, in which she is neither qualified nor honest enough with herself to deal with, in pot-shot Tweets and logic-challenged essays. Again, the proper place for an author to work out such issues might just be the tools at hand, that have worked so well: a big, fat book.

This is not, by the way, a “stay in your lane” argument. Had J.K. Rowling researched and written a big, fat nonfiction book on the gender issues that so trouble her, which she haphazardly connects to her own fraught identity issues, she may very well have come to very different conclusions than her still-muddled and destructively expressed biases and bigotry; at least there would be a substantial document and bibliography of documentation to debate. Instead, we have an even worse product than either The Cursed Child or Fantastic Beasts: the sketchy, patchwork, transphobic nightmare world of Joanne Rowling.

The shame of it all is that the most poorly-thought out

ideas of this most successful of author are having the most direct consequences

in our real world. It’s one thing for a stage play or a film franchise to be

based on the half-baked leavings of a once scrupulous and wordy author; it’s

another for her most uninformed opinions, gobbledygook nonsense, and hateful pronouncements

to be injected directly into public debate and social media misperception. If

nothing else, those big, fat, immersive and all-consuming fantasy books would

keep her from greater mischief.

_____________

* See my other blog posts about my time at Borders as a sales clerk during the heyday of Harry Potter, as well as Rowling’s self-reinvention as a hateful transphobe.

Read the Ms. Megaton Man Maxi-Series! New prose chapter every Friday!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments from anonymous, unidentifiable, or unverifiable sources will not be posted.