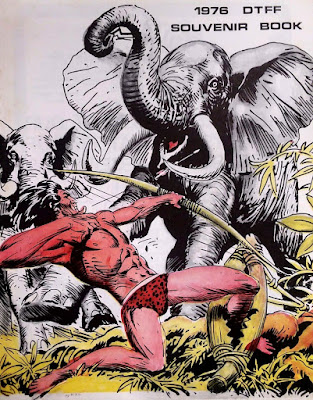

The first comic book conventions I ever attended were primitive affairs: the 1976 Detroit Triple Fanfare, in the downtown Book-Cadillac Hotel, was little more than a swap meet of bare tables, cardboard boxes, and hippies selling fanzines and back issues of Barry Smith’s Conan the Barbarian. The sole comics professional guest was Joe Kubert, set up in a crowded side-room that as a fourteen-year-old exclusively Marvel fan, I decided to skip.

The monthly Fantasticon, a suburban show held at the Sans Souci at Nine Mile and Middlebelt, was a similar affair, only smaller, with local talent: Skip Williams, Mike Gustovich, Bill Bryan, and T. Casey Brennan—most of whom were affiliated with Power Comics, a Michigan ground-level company.

In those days, comics reading and collecting for me was not a social activity. After the summer of 1972 when my friend Brad Hogue outgrew comics, I was on my own—biking up to Seven Mile to Greene’s Pharmacy (because they had the better spinner rack than Howard's Drugs at Six and Inkster), and later, to downtown Farmington at Grand River, where Jerry’s New and Used Books and the Classic Movie and Comics Center (along with the Art Alcove, the shop I where I bought Speedball pens and Bristol board) became my cultural center.

By the time I broke into the industry in the mid-1980s, comic book conventions had become integral to the profession of comics creation. At first, “Artist Alleys” were merely sideshows at the monthly Chicago Mini-Con at the Americana Congress. There, an artist like myself, with a semi-hot book like Megaton Man, could make ten or twenty bucks a sketch; an art student like nineteen-year-old Jill Thompson, who worked a table wearing a coin changer, could watch me and a dozen other pros ink with sable brushes and pepper us questions on tools and technique. By the end of the eighties, Artist Alleys had morphed into a major source of revenue for for artists to sell not only sketches but original art, back issues, and new comics the distributors and shops couldn’t or wouldn’t carry.

At the same time, major shows like Chicago, San Diego, and Dallas morphed into places where the big New York companies, at least DC, could get out of New York and confer amongst themselves—they became almost editorial retreats; a summer show might be the only time some freelancers and editors ever saw one another face-to-face, discuss assignments in the hotel bar or restaurant. The same applied to smaller publishers and independent creators. I can still recall passing Frank Miller, seated at a table with somebody—perhaps Mike Richardson—in the crowded Panda Inn in San Diego, while I was being seated along with Eclipse publisher Dean Mullaney and Fantagraphics publisher Gary Groth.

|

| The Joe Kubert Tarzan cover to the Detroit Triple Fanfare booklet, the first con I ever attended. |

Marvel, headed in those day by Jim Shooter and subsequently Tom DeFalco, cultivated an air of aloofness and arrogance that was palpable; staffers like Bobby Chase and Peter David looked down their noses at the indy creators (although some, like Carol Kalish and Ron Frenz, were naturally friendly and gregarious, even to us lowly heretics). But DC used the opportunity to head-hunt for indy talent; folks like Mike Gold, Mike Baron, Steve Rude, Bill Loebs, Sam Keith, myself, and many others were practically shanghaied at such shows—perhaps all at Chicago—without ever submitting a sample through the mail. These recruitment drives fueled DC’s artistic resurgence in the eighties and rostered their subsequent Piranha and Vertigo imprints.

By the 1990s, cons had gone from being somewhat optional for professionals to a professional obligation—if you weren’t attending Chicago, Dallas, San Diego, Procon and Wondercon in Oakland, and at least two or three other national or regional shows every season, you risked being forgotten—not only by the comics collecting, buying, and reading public, but by the editors and publishers for whom one might hope to freelance or create. On top of this, the distributors Diamond and Capital as well as San Diego each added one major annual trade show a piece, a must for self-publishers who wanted—and needed—to network with the approximately six hundred retailers who actively supported indies.

By the time the Direct Sales market collapsed in 1996, everyone was exhausted—myself first and foremost. I didn’t even try to fight forced early retirement; I went online with my Megaton Man Weekly Serial, a pioneering web comic, but was otherwise out of comics. For the next several years I sought gigs as a graphic design freelancer locally, worked as a part-time clerk at Borders Books and Music, and finally went back to college.

By the mid-2000s, everyone was giving out industry awards: the Eisners or the Harveys or the Kirbys. Paul McSpadden’s Harvey (Kurtzman) Awards moved to Pittsburgh, my backyard, in 2004, along with half the industry; as a casual con attendee and old acquaintance of Paul, I was asked to hand out the coloring award. Just a few short years later, the promoter of that show, Mike George, was charged and convicted of murdering his first wife, Barbara, whose show I had once attended in Michigan.

By the mid-teens, the nature of publishing had shifted away from old web printing presses (web in this sense meaning giant rolls of paper run through machines with liquid-inked printing plates, not the World Wide Web) to print-on-demand. Being a self-publisher was no longer an act of defiance against the major companies, but s caeer ploy to (hopefully) catch a New York editor’s attention. At the same time, Kinko’s and later Fedex Office and Staples, along with countless other photocopying places, led to a flourishing of prints and booklets. Numerous small press expos and “zine” cons were everywhere, and the very idea of a comics “professional” as a concept determined by gatekeepers like newsprint comics printer World Color Press or even Baxter paper printer Ronald’s/Quebecor lost all meaning.

In the meantime, table space in Artists Alleys, once free to working pros, had morphed into profit centers for cons; cartoonists and self-publishers now had to buy their way in if they wanted access to the public (or New York editors). Artists now were not only competing with back-issue dealers or even publisher booths, but celebrities, professional wrestlers, and cosplaying contests—all bigger attractions as far as the public was concerned, as “comics” became a synonym for a kind of superhero content associated with big-budget movies rather than hand-drawings reproduced by analog photolithography on paper.

Thankfully, I was out of the business at this point.

Now, we are approaching the mid-2020s. “Shows” have replaced “cons” as the favored term, and it has become almost impossible to tell which event might be something akin to an old-school back-issue swap meet with a pro Artist’s Alley comic con, and which are merely “pop fests”—where most attendees are waiting in line to get their picture taken with a taxidermied Leonard Nimoy or dressed up as Deadpool or Harley Quinn. It is a well-known fact among cartoonists that cosplayers have no pockets, and don’t spend money on comic books or convention sketches anyway.

I’ve been lucky since my post-PhD career to be invited to a number of shows within driving distance of Pittsburgh. Most have been what I would term “comic art-friendly”—catering to fans, readers, and collectors of comic books, graphic novels, and original art—although most have contained more than a heavy dose of cosplay and celebrity adulation.

However, post-pandemic, I’m wondering if any shows, even ones that still call themselves comic cons and try to offer robust pro Artist Alleys, can resist succumbing to the pop-show event model.

This was brought home to me last weekend, when I attended a self-billed “comic con” show boasting a pro guest list. None of the pros, however, were under the average age of sixty, and none of the fans who stopped by my table seemed under forty. Out of over 300 booths (no one shows up at a show with just a bare folding tables, as they did in 1976!), fewer than 10-20%, it seemed to me (honestly, I didn’t count—although my brother affirmed it was no more than a quarter), were purely comic book back issues; significantly, no original art dealers at all were in attendance.

In fact, there wasn’t a discrete Artist Alley as such at this show. Guests were aligned along one major axis, but it included Star Wars cosplayers and droid builders along with comics writers and artists. After I complained about the incessant, shrill, and piercing droid sound effects on a ninety-second loop directly across from me (that could be easily heard a row over) to two different show staffers, and hours later told off the 501st Legion for the lack of consideration for their neighbors (all of whom create original content rather than anonymously impersonate corporate trademarks), the promoter finally showed up at my table and told me point-blank I could shut up about the droid loop or pack up and drive home 300 miles (with the inference that he was about to toss me out on my ear anyway).

Ah, the glamorous life that is being a legacy comics professional!

It was then that I realized what a vulnerable positions comics is truly in. I’m used to the tail wagging the dog, and being in the minority; to be an indy creator in the 80s and 90s meant attending shows where Marvel, DC, and later Image and Dark Horse were the giants (let’s not forget scream queens); to attend shows in the twenty-first century, it meant being outranked by celebrities and professional wrestlers. But droid sound effects on a ninety-second loop from a CD anyone can buy online (and of course can see in the movies)?

It is my observation and prediction that after this season, shows will be scrutinizing their bottom lines and asking themselves if Artist Alleys and pro guest lists make any rational economic sense. Are lovers of the cartooning arts, readers, and collectors bothering to brave shows that are little more than cosplay contests and blaring media hypefests? (My communication with fans on social media tell me otherwise; many told me this season to hell with it.) Are aging creators like myself going to bother traveling any distance to be treated to a barrage of noise, chaos, and confusion, only to be lost in a crowd of toy booths (and bullied by promoters fearful of losing their crowd-pleasing 501st Legion of anonymous Boba Fett impersonators)?

This is not a lamentation or a complaint at this point, and I don’t take the current state of affairs personally. (I for one would have loved a career drawing away in my attic, like Carl Barks, coming out only after decades of anonymity to recreate favorite Uncle Scrooge covers in oil on canvas.) One could argue that the only reason comic book companies stayed around in American culture at all after the 1950s was to serve as licensors for toys, TV shows, and movies. The American comic book has been in a transitional state of disappearance for more than my lifetime, and those who have taken the art form seriously in one way or another have always been fighting an uphill, and losing, battle.

When even “shows” that proclaim themselves to be art-friendly “comic cons” are actively, militantly hostile to comics and their creators—because their bread is buttered by anonymous movie extra impersonators who’ve been close to a movie set in their lives (and by the way, an authentically-built R2D2 would be completely silent; the shrill screams, chirps, and whistles were all added post-production, you morons), the artform of the American comic book has reached a new level of disappearance.

Read the Ms. Megaton Man Maxi-Series! New prose chapter every Friday!

If you’re on Facebook, please consider joining the Ms. Megaton Man™ Maxi-Series Prose Readers group! See exclusive artwork, read advance previews, and enjoy other special stuff.

___________

All characters, character names, likenesses, words and pictures on this page are ™ and © Don Simpson 2022, all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments from anonymous, unidentifiable, or unverifiable sources will not be posted.